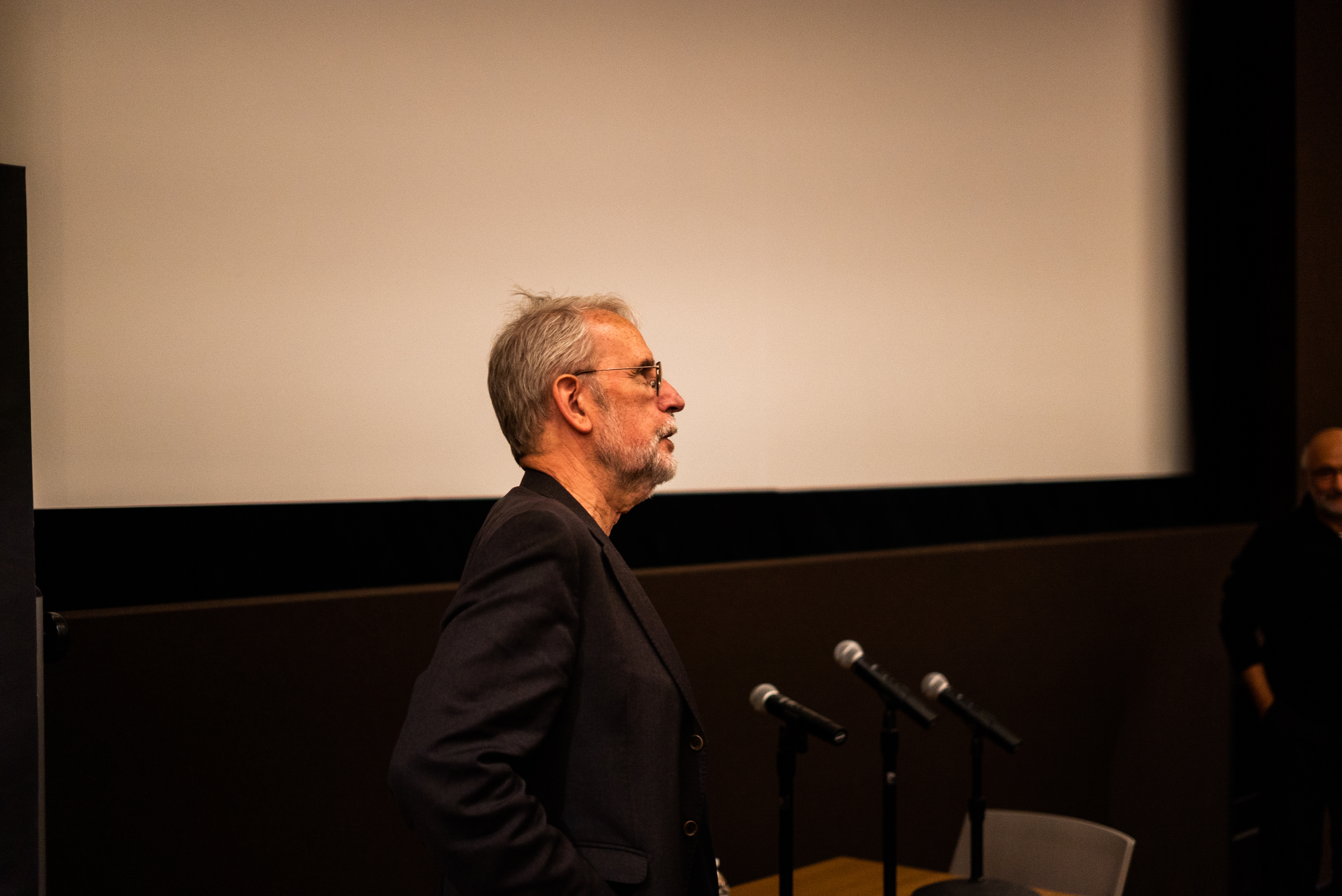

On the nascent years of film editing...

Auguste Lumière, one of the inventors of cinema, considered the new medium an “invention without a future.” Murch explained that Lumiere held this conviction because the inventor didn’t truly understand editing. Murch goes on to describe what was then a revolutionary idea: “You can shoot stuff in a different order than it will eventually appear, and you can take these shots and cut them together, and the audience will consider that leap as continuous reality.”

The prospect of editing meant that early films could evolve from single-shot videos that, while amusing, only briefly held a viewer’s attention, to something with a more traditional narrative arc.

On Margaret Booth, an influential film editor who brought status to the role…

Booth was Louis B. Mayer’s primary editor, a role that earned her a reputation for striking fear in the hearts of other editors. “If she knocked on your door and said, ‘Get out,’ you got out,” Murch said. “She and her team would move in and take over a film and edit it according to her sensibility, which was something that the head of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer agreed with. They were a tag team: bad cop and bad cop.”

This reputation would ultimately alter the future work of filmmakers who had interacted with Booth. Murch was working on Fred Zinnermann’s Julia when he noticed that when Jane Fonda would walk through a doorway offscreen, and Zinnermann would yell “Cut,” Fonda would come to an abrupt stop. “All the actors did it. It was like they had been trained by Fred to do this,” Murch said. He explained that this ran counter to the traditional practice of letting the tape roll for a few extended beats. Eventually, Murch popped into Zinnermann’s office to quell his curiosity. In his response, the director referenced his work with Booth and MGM: “If I did that (let the tape roll), then [Margaret Booth] could take my film and then recut it, because on the other side of that closed door she could have a new scene. When I went to see the movie in a theatre, lo and behold it would be something I didn’t direct.”

The filmmakers who worked throughout the ‘30s, during Booth’s emergence, learned to “cut in the camera” to make it as difficult as possible for the studio to interfere with their vision for the film.

On living in the analog world of film editing…

Murch’s career has traversed the analog and digital eras of filmmaking and editing. To convey the physical limitations of the analog age, the editor described searching for a two-frame clip of film from Apocalypse Now, a film with 236 hours of original material.

“A thousand feet of 35mm picture and sound lasted 11 minutes. Conveniently, it weighs 11 pounds. It turns out to be a pound a minute. Apocalypse Now was 14,160 minutes, which equals 7 tons of [footage].” To track down the physical clippings, Murch would navigate corridors filled with storage and numbered systems that would eventually lead him to the material he was looking for—a far cry from the literally weightless systems of the modern digital era.

On his advice to young filmmakers…

Murch emphasized a series of thoughts to consider when taking on a new project: “You have to find the invisible umbilical cord that connects you to the material. Does the subject matter push you out of your comfort zone? Do you think, I don’t know if I can do this?”

The editor considers comfort a dangerous environment for a creative endeavor. “If you’re too comfortable, you fall into tropes that repeat themselves over and over again. That will deaden a film.”

Next, he assesses the interpersonal working environment. “Can you get along with the people?” he asks himself. While acknowledging that there have been some successful projects that emerged from unhealthy work dynamics—and that friction can occasionally benefit a project—Murch also encouraged filmmakers to trust their intuition.

Finally, Murch touched on the overall viability of the project, namely the financial support, the creative oxygen, and the structure of the team. “Do you get all three of those things simultaneously? Maybe not. Sometimes you have to make a guess.”

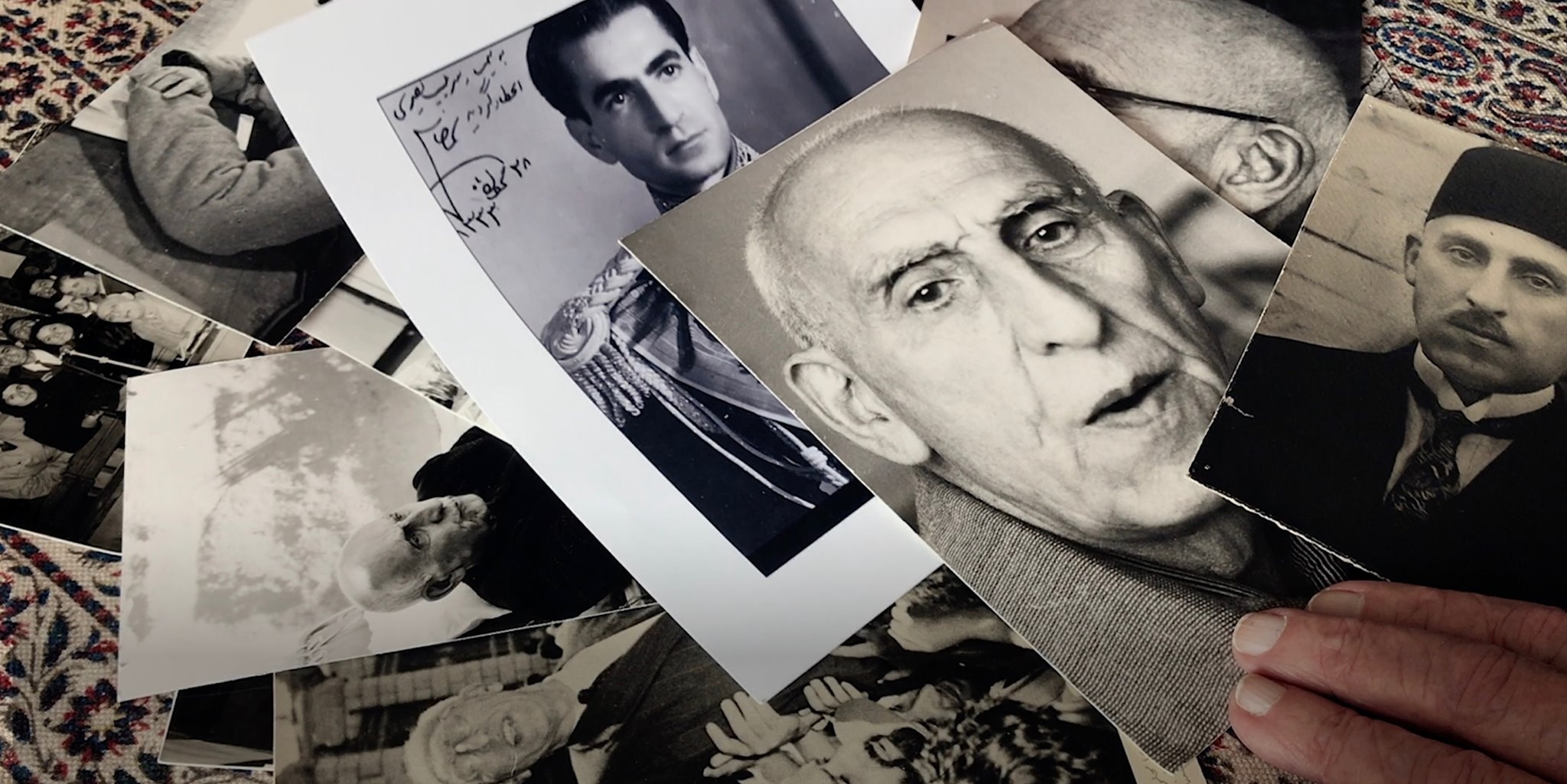

For upcoming news about director Taghi Amirani’s “Coup 53,” visit www.coup53.com.