Until last year, Alice B. Russell Micheaux, the pioneering African American filmmaker and actress whose contributions to the black filmmaking canon have been largely overlooked, lay resting in an unmarked pauper’s grave with nothing more than a slight mound to indicate its presence. Unfortunately, it was not an exceedingly unusual case of a forgotten and ignored African American life, even for one as influential as Micheaux’s.

A remarkable life, and yet an unremarkable preservation of it. These themes collided with regularity at last week’s Black Portraiture[s]: V: Memory and the Archive Past. Present. Future, organized by NYU Tisch Department of Photography and Imaging Chair Deb Willis.

Speaking on a panel about Micheaux, Black Film Center/Archive director Terri Francis retraced her own efforts to remember and repair the lost history of this seminal artist. Through her research, and with the help of a successful GoFundMe campaign, Francis spearheaded the placement of a headstone at Micheaux’s grave and organized a memorial service that the artist likely never received following her death in 1985.

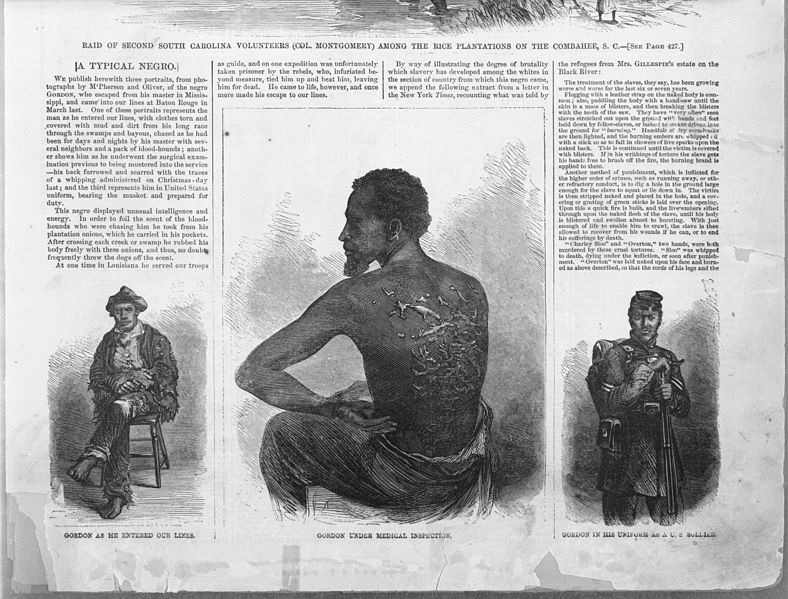

Francis is one of more than 200 scholars, artists, curators, and other researchers who converged on NYU for the ninth edition of Black Portraiture[s] (Oct. 17-19), an itinerant series about imaging the black body. The latest iteration of the conference comprised 50 panels that examined the archive of the African Diaspora from perspectives of accessibility, maintenance, control, subjugation, and plenty more.