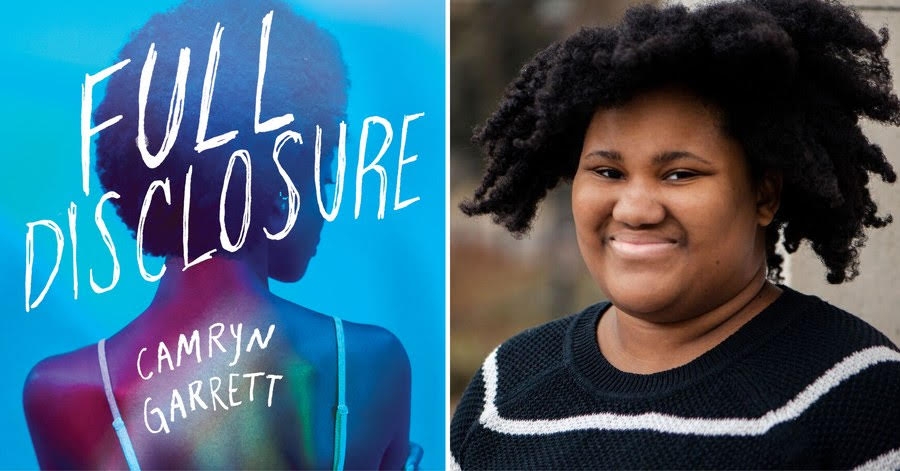

Camryn Garrett’s new entry to the young adult fiction genre is—like its protagonist—a beautiful outlier. Sure, there are your YA mainstays: romance, sex, an abundance of social blunders. But there is also a refreshing and uplifting take on the coming-of-age novel. In her authorial debut, Garrett invigorates the often harrowing world of AIDS narratives with a heartfelt story told by a hopeful and trusting voice.

Full Disclosure is the fictional story of Simone Garcia-Hampton, a black teen born with HIV wading through the anxieties and awkwardness of adolescent life. That prospect, daunting on its own, is complicated by her attempts to keep her diagnosis under lock and key. When Simone falls for a boy at school named Miles and the pair’s relationship begins to blossom, an anonymous note threatens to unmoor her from the safety of her secret. Confronted with newfound curiosities about sex, self-acceptance, and transparency, Simone begins a journey of discovery with the loving support—in all of its humor and cringe—of her queer parents.

Garrett is currently an undergraduate student at NYU Tisch’s Kanbar Institute of Film & Television. Full Disclosure, her debut novel, is available now. Follow her on Twitter at @dancingofpens.

NV: I imagine a lot of people would agree that this subject matter is always in need of vibrant new voices. There may be a million “easier” stories to tell, but this is a story that needs to be told for this generation. What provided you the conviction to tell it?

Camryn Garrett: The hardest part is reading about people who passed away due to complications from AIDS—that is really hard for me. I try not to think about it because it makes me really emotional. I was drawn to [the subject matter] because I didn’t know anything about it and I felt like no one else in my school my age knew anything about it. Even a few weeks ago I was wearing a shirt from ACT UP, an activist organization, and my friend [asked about it]. And I said, “It’s about the AIDS crisis,” and she said, “What’s that?”

NV: Wow.

CG: Yeah. And so I was asking other people because I was doing this little experiment to see if it was just her or if it was a thing. And people were like, “Umm, I’m not exactly sure…” So now, and even when I was in high school, it wasn’t something that we really knew about, and that made me really upset, which is why I wanted to learn more about it. There is such a stigma—even the history associated with it. I feel that it’s very important, and it’s such a shame that a lot of young people don’t know about it.

NV: The novel seems to radiate positivity. From the sex-positive conversations to the supportive father-daughter relationships, why was it important to you to capture that outlook?

CG: When I was doing research, I did a lot of nonfiction academic stuff, but I also watched a lot of fiction about HIV and AIDS. A lot of it was very true and accurate, but also really sad and depressing. It was written during the height of the crisis in the United States. A lot of it was, “Everyone we love is gonna die” and “there’s no hope.” I hadn’t really seen a novel about the modern day reality. There are so many medical advances, so I think the biggest thing is stigma—that’s one of the things we can actively change. So I wanted to write something uplifting because I felt like I didn’t see that.

Not only my main character, but other young people deserve to see this story and the normal things happening to people with HIV—them falling in love and having sex.

NV: I fell down a rabbit hole reading your Twitter over the last few days and it conveys the very honest, daring, and funny young writer that you are. How much of that is infused in Simone?

CG: There’s a lot. It’s interesting because she’s different than me. She’s more outspoken about things that I’m not necessarily. The way she talks about sex in front of her parents and to her parents, I never ever do. I gave my friend an early copy of the book, and she said, “Sometimes when I read the dialogue, she sounds just like you.” It’s hard to not put little parts of yourself in.

NV: Our own fears are often major threats to any creative pursuit. What would you say to another young creator who’s confronting feelings of doubt?

CG: This is hard, because I still worry about it. I think everyone worries about it all the time. I definitely don’t think family members would agree with me, but I feel like you’re meant to do what you’re meant to do. If people are stressed out about that, which is perfectly valid, you can go to school or get something that you know will be your day job, and then work on your art on the side. But I feel like if you’re meant to be an artist, you’re going to be an artist—even if it isn’t practical, even if everyone thinks that you’re silly. It’s who you are, and I don’t think you’ll be fulfilled without doing it.

NV: And you’re also studying film at Tisch. What are your plans for the future and what can we expect from you next?

CG: I want to keep writing books, but I also want to write and direct… I’ve kept my eyes on [Stephen Chbosky], because he wrote [The Perks of Being a Wallflower] in 1999 and ended up adapting it into his own film. He wrote the script and directed it, and I thought, Wow, that’s so cool, I didn’t know you could do that. And since then he’s directed Wonder, and he directed a few films that have nothing to do with his books. I like the idea of adapting your own work, or not, and just making films and then writing things and just having the freedom to work in either medium. They both offer different things, and I really like that.