In the late stages of the Information Age, the convenience of technology has given way to a restless hand-wringing over digital privacy. As our lives migrate online, so too do the data points that define us. But even as deep anxieties swirl around the overabundance of digital information, there remain persistent gaps and absences in how data systems represent many people and communities. Where one community is preoccupied with individual privacy, another may be left behind by the modern methods of data collection. How do we move toward a more equitable world when the technology of today neglects the communities on the fringes?

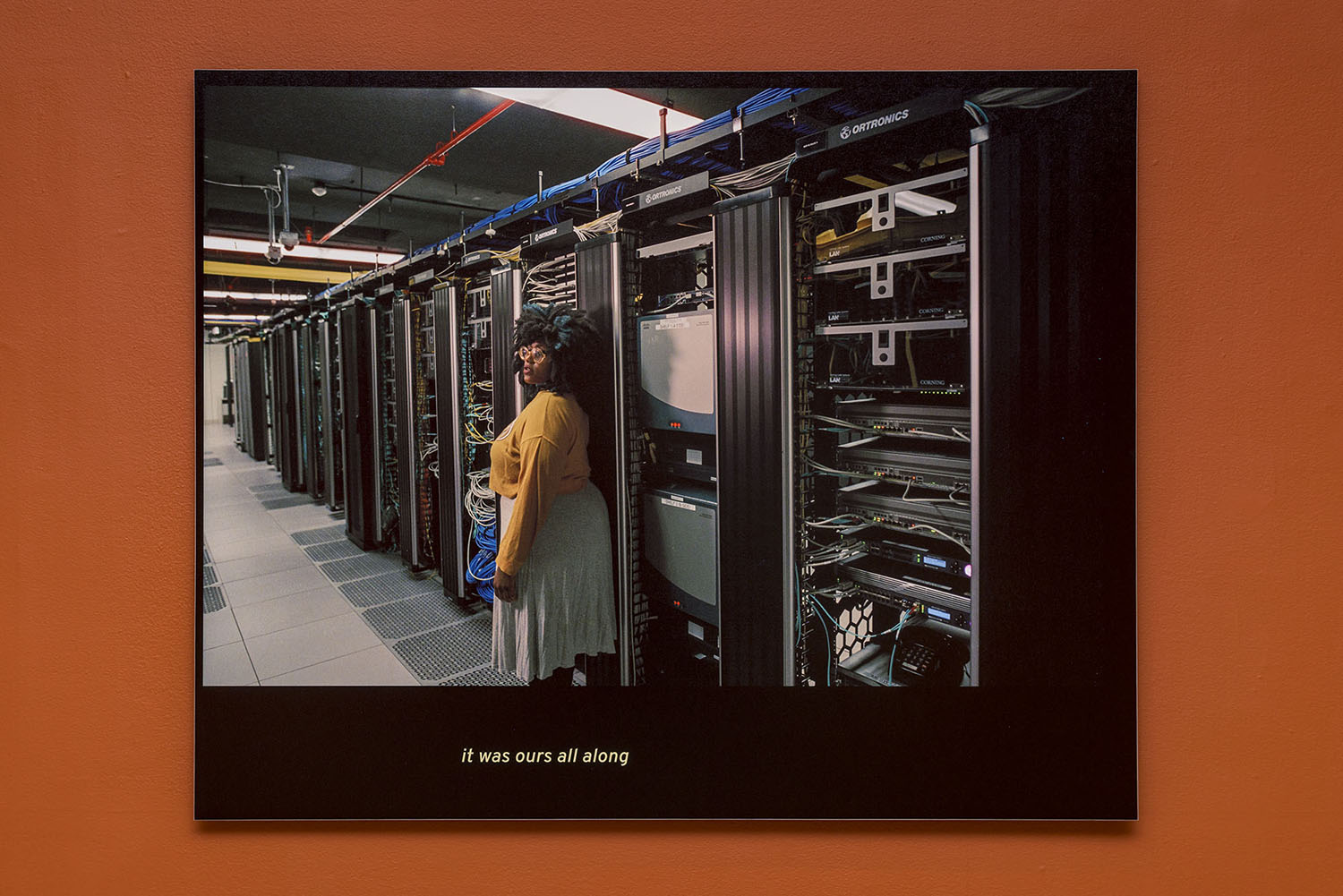

In Everything That Didn’t Fit, a new bitform exhibit from NYU Tisch ITP alum and former visiting professor Mimi Ọnụọha, the multimedia artist and researcher traverses physical and digital spaces to bring into focus the people and stories who are repeatedly left out-of-frame. She revisits a century-old W.E.B Du Bois research report on Black rural life (“In Absentia”), probes Black women’s proximity and relationship to data via a series of photo prints (“Natural: Or Where Are We Allowed to Be”), and uses installations to make tangible the data erasure that is obscured by complex technologies.

In every case, we see that these absences disproportionately affect Black, queer, and immigrant communities. Working together to unearth these gaps, Ọnụọha’s diverse collection becomes an almost overwhelming depiction of who has been left out, and how these socio-technological systems fail to paint a full picture. We recently spoke with Ọnụọha to discuss the origins of her research and artistry, the challenges in visualizing the abstract, and how she glides between mediums to tell stories.

Learn more about Mimi Ọnụọha’s exhibit Everything That Didn’t Fit, showing at bitforms through March 5.