In a sports-obsessed American culture dominated by the “big four”—that is, the NFL, NBA, MLB, and NHL—boxing has become the plucky dark horse. Once considered a tentpole fixture in the events calendar, big-time fight nights have slowly retreated into the background since boxing's golden age—a heyday marked by spectacular heavyweight competition in the 1970s and ‘80s. Despite surges in popularity since, boxing has struggled to reenter the public psyche with the zeal it once had. The sport for underdogs, in certain circles, is now the underdog sport.

It can be easy to cast aspersions on a discipline that, to the untrained eye, presents as crude violence sublimated into sport. Still, “the sweet science,” as it's affectionately known to devotees, seems to struggle disproportionately with earning widespread respect. Could it all be a misunderstanding?

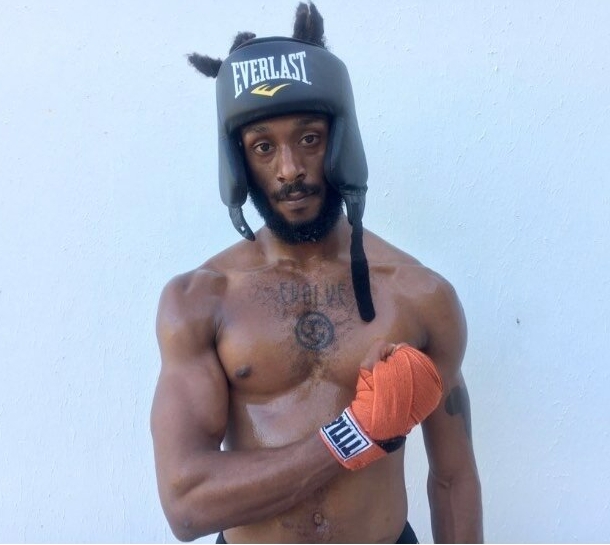

Zac Easterling (they/them) is a Ph.D. student in the Tisch Performance Studies program who is leveraging their years of boxing experience to expand the way we think about the performance and tradition of pugilistic arts. Easterling currently coaches at Trans Boxing, an ongoing co-authored art project in the form of a boxing club that centers trans and gender-variant people, and elevates the community-building and educational elements of the sport. We recently connected with Easterling to learn more about their academic approach to boxing, the sport’s intrinsic ties to performance theory, and the value of inclusivity in a boxing club.

Describe for me your journey to the Performance Studies program and the focus of your work.

Zac Easterling: I came to the Performance Studies program after getting an M.A. in ethics and applied philosophy at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte—I'm originally from North Carolina. But, you know when you’re young and you're kind of like, Academy is stupid, I’m going to move across the country and try my hand at boxing all the time? [laughs] I did the M.A. and then I moved to Seattle and I boxed like it was [my job]—six days a week I'm in the gym, I have a coach, I’m sparring three days a week. And I do that for about a year, and in the course of that time I kind of was missing school.

I [began to think] about programs that would be conducive to my background. In my M.A. I studied critical race theory and Black studies and I had started writing about boxing during my philosophy M.A. I wanted to focus on Black studies and boxing, and Tisch’s Performance Studies Department seemed like the spot to do it.

And where along this path are you now?

Zac: I originally came for the Performance Studies M.A., which is a one-year program. And now I’m a second-year PhD now.

Being in New York has been great just because it’s known as the boxing mecca. That's part of the reason I wanted to go to NYU—if you're a scholar of boxing you should go to New York.

What are the seeds of your current relationship and work with Trans Boxing?

Zac: I started with Trans Boxing during COVID. I called up Nolan Hanson, who is the founder and had started it as part of their MFA project that they were doing in Portland. I became aware of it because of some overlapping circles of people. I just called them up on the phone one day and was like, “Hey, what's up!” And [Nolan] was like “Oh, I already follow you on Instagram, man.” [laughs]

So we started chatting and they put me on with their coach Carl Westbrooks, who's out of New Bed Stuy Boxing Gym, which is a legendary gym. Riddick Bowe and Mark Breland came through there. The founder, George Washington, had over 100 professional fights with like 80 knockouts or something crazy like that. It was just one of those things, as a scholar of boxing or however you want to frame it, it’s just a good place to be at.

In many ways we can think about boxing as a tacit exercise in performance studies. Do you find that people underestimate the performance and theory inherent to the sport?

Zac: It's almost like everybody underestimates boxing—including boxers. I think the NYU performance studies program is good about not really allowing a distinction between high art and low art and popular art. When that distinction is discussed, it’s challenged.

I feel like I get a lot out of doing performance studies not only about athletics, but about the particular form of relationality that's there within boxing. There are a million stories that you can tell in the ring or outside of the ring. And this is really where I think boxing is like a method of study, as opposed to just studying boxing. With my experience I am able to see and comment upon and do the particular kind of study that I want to do as a PhD student.

As someone who boxes and trains people how to box—or even when I talk to people who are more experienced than me—it’s almost like they don't realize how much they're theorizing all the time. They’re doing super rigorous, interesting theory, and maybe they're just talking about the next fight they want to watch. But it's just like, oh man, they’re obviously theorizing race and relational intimacy. They have these really novel takes that you really wouldn't expect of them—or they wouldn’t expect of themselves.

We've all underestimated what boxing can be for us. And I think that's what I'm trying to be hip to. If there's some novelty to my research, it’s that.

There is a community building element to each boxing gym, but Trans Boxing is directly oriented around inclusivity. What does that look like inside the gym?

Zac: Trans Boxing is a club that operates out of multiple spaces. So there’s nomadism there. Right now we’re always at Overthrow on Bleecker Street on Saturdays. But some people like Nolan and I are really tied to New Bed Stuy, where a few others of us train.

So, we’ll be in between places. It’s good because it allows people to find a way into a gym that they might not have wanted to go to on their own. It’s like, “No we’re all rolling up here, all the gays are going to be here, we got it” [laughs].

The point is inclusivity. We don’t want this to be thought of as trans-only as much as we want to center these participants so that everyone can feel welcome.

Right, you want the gym to reflect the community in full.

Zac: Exactly. And you know, a part of Trans Boxing is also theorizing through race and through relationships more broadly. So being able to be in these different places that attract different fighters [is important].

Boxing people aren't that common really. Boxing is coming back into the public forefront, but who’s training and sparring and trying to be in shows? And then who’s trans amongst them? It's a small community and you see people really come into their own.

I get most excited about seeing people who are ranked amateurs and are very timid and see how they become more confident fighters. How do they take that confidence into their life and their performance of gender and their ability to feel confident in themselves?

How do you envision working to merge these academic and physical spaces in the future?

Zac: I'm about to go into my reading semester so I’m starting to think about what my dissertation is going to be. I’ll finish my PhD, but who knows what will happen after that! My life is somewhere between philosophy and boxing. Whenever opportunities present themselves where I can have enough time for both, that’s the way I'll go.